Donate Online:

Cash App: $tciguyana

Zelle: donate@citizenship.gy

In Guyana: Please contact us

PILLAR - Participatory Citizenship, Enhanced Governance and Public Accountability

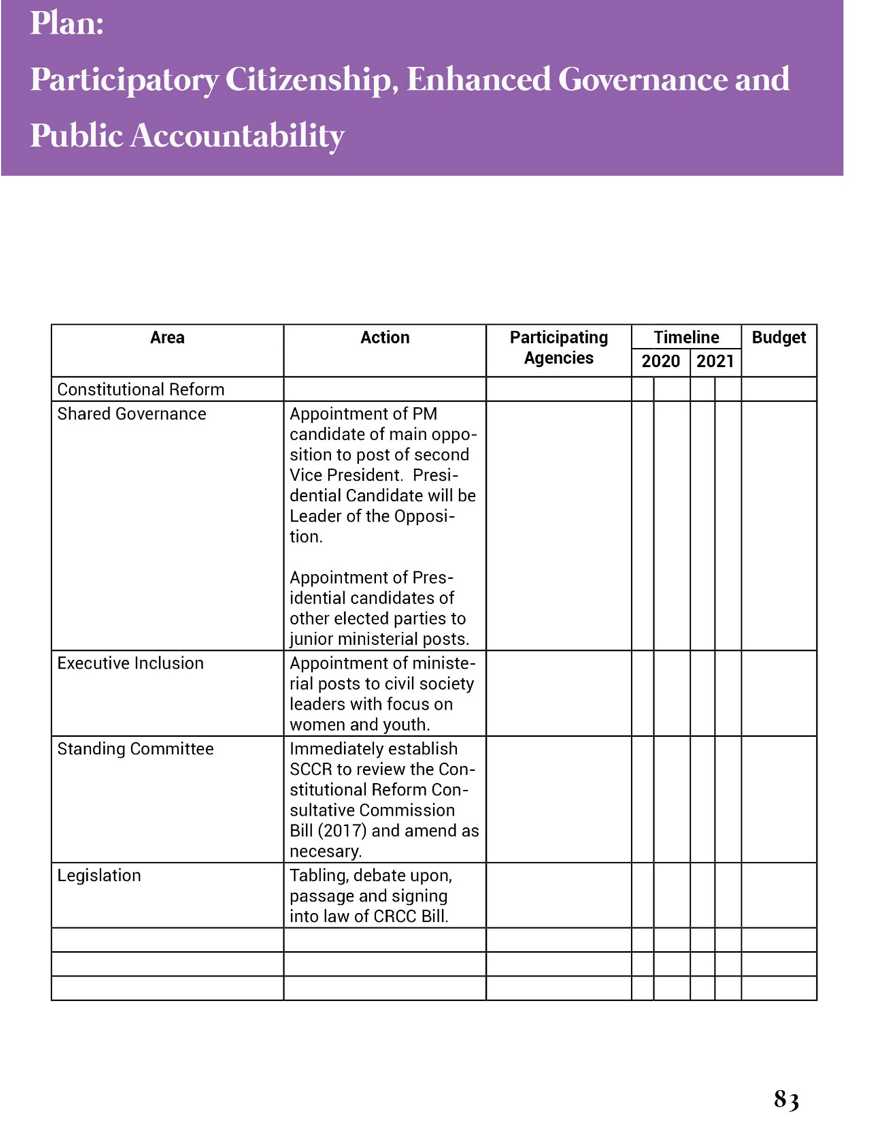

Constitutional Reform

In 1980, the government of Guyana under Forbes Burnham implemented a new Constitution, a document that emerged from a referendum that was widely known to have been rigged. That constitution established a powerful executive presidency and a parliament that had no powers to curb that power.

When the PPP rose to power under Cheddi Jagan in 1992, it was with a commitment to reform that constitution, reforms that had not taken place at the time of Jagan’s death in 1997 with only minor amendments in 1996. In 2001, a bipartisan reform process that started in 1999, culminated in the only significant reduction of the powers of the presidency being a limitation to two terms in office of any individual.

Over the past ten years, both major parties have openly supported constitutional reform, primarily while in opposition. For example, APNU – led by now President David Granger – made the following commitment in its 2011 manifesto: “Undertaking constitutional reform to remove the scope for abuses and excesses carried out with impunity by the Executive and by the President, in particular.”

The coalition opposition – again led by now President Granger, with the AFC’s Moses Nagamootoo as Prime Ministerial candidate – in its own 2015 manifesto made even clearer commitments:

“APNU+AFC recognizes that the Constitution, in its current form, does not serve the best interest of Guyana or its people. Within three months of taking up office, APNU+AFC will appoint a Commission to amend the Constitution with the full participation of the people. The new Constitution will put the necessary checks and balances in place to consolidate our ethos of liberal democracy. Freedom of speech, reduction of the power of the President and the Bill of Rights will be enshrined in the document.”

Two things happened towards the fulfillment of this promise: a group of experts was commissioned in late 2015 to undertake a report on recommendations for the establishment of a commission to steer the constitution reform process, the report being submitted in April of 2016; in 2017, a year later, a bill, the Constitutional Reform Consultative Commission Bill was presented to the National Assembly but was never debated nor put to vote. The result is that, with the elections of 2020 approaching, the coalition administration that campaigned in 2015 with a commitment to constitutional reform has not done anything substantial toward actual constitutional reform.

In November of 2019, former president and leader of the PPP opposition, Bharrat Jagdeo, made his own commitment to constitutional change, a process that he displayed no desire for except in his attempt to reverse the very term limitations that took place in 2001.

The reality is that both sides have had a tacit agreement to not advance constitutional reform. Since the initial reform processes of 2001, there has been in fact a Standing (permanent) Parliamentary Committee on Constitutional Reform.

For the 11th Parliament (2015-2019), that committee comprised of Basil Williams (Chair) Dr. Rupert Roopnaraine Raphael Trotman Khemraj Ramjattan, and Nicolette Henry for the coalition and Priya Manickchand, Anil Nandlall, Frank Anthony, and Adrian Anamyah for the opposition. In the three years leading up to the No Confidence Vote of 2018, that committee met no more than five times with no great objection from either side.

As one international agency concluded in a 2018 report on the possibility of constitutional reform:

“…the governing coalition and PPP/C may both go along with the constitutional reform process, but in the end fail to adopt the most needed amendments. As previously stated, both parties believe they stand to win the 2020 election. And both parties have historically enjoyed (i.e., failed to reform) the excessive executive powers under the 1980 Constitution…. The risk is that both parties might pay lip service to constitutional reform and adopt some amendments on the margins, but in the end fail to pass any of the most needed amendments, thereby maintaining the status quo.”

For the Citizenship Initiative, the next steps are fairly simple. If elected to government with a majority in the legislature we will immediately appoint our members to the Standing Committee on Constitutional Reform; review (and amend if necessary) the Constitutional Reform Consultative Commission Bill; establish the Commission with full and adequate funding and a mandate to engage in national consultation; develop and execute a national constitutional and civic education campaign complementary to the Commission’s consultation; draft a new constitution based primarily on greater devolution of power to the people; seek a two-thirds majority in the national assembly to pass it and failing that undertaking a referendum.

There is no reason that this process should go beyond 2022 as the previous constitutional change processes, 1978-1980 and 1999-2001 have demonstrated. It is our intention that the next general and regional elections will be conducted under a radically different constitution than the one we are currently burdened with.

While we will not preempt the representations made by the citizens of Guyana during consultations, we have the following menu of key measures we will be advocating for in the new constitution:

- Drastic reduction of the powers of the president along a spectrum that ranges from the abolishment of the position to the retention of the position but subject to clear and unequivocal mechanisms of censure and removal by the National Assembly.

- Establish a mechanism for shared governance, with a formula that gives the representatives of the people a greater say in executive decision-making, and a greater influence over executive decision-making, than obtains at present.

- Abolishing the list system to a more direct constituency-based democracy, one that removes the current hurdles for participation by emerging independent political leadership.

- The complete structural depoliticisation of the Guyana Elections Commission and establishment of a professional organization with a mandate to ensure that all processes of the institution are subject to public scrutiny.

- Deepening constitutional guarantees for the role of women in political leadership, raising the constitutional threshold for party representation in national elections from 30 percent women candidates to 40 percent.

- The inclusion of constitutional guarantees for youth involvement, similar to the current gender quota, specifically the constitutional provision that party representation in the national elections must include 30 percent of candidates 35 and under.

- Constitutional guarantees for basic housing and shelter for all citizens of Guyana, and guaranteed access to land ownership for domestic use, particular as a priority over land acquisition by foreign actors.

- A tiered/hierarchical constitutional pathway for the inclusion of dual citizens – particularly Guyanese diaspora – in the national assembly.

- The expansion of fundamental rights and the expansion of constitutional protection against discrimination to include persons with disabilities and LGBTQ persons. Additionally, in keeping with the increasing role of information technology in everyday life, we intend to advocate for the right to WiFi as a basic right, as well as the right to digital privacy, including protections against unsanctioned surveillance and clandestine, non-consensual acquisition of personal data by either private or public entities.

Guyana has not benefited from the winner-take-all politics. It is time we move beyond lip service on constitutional reform and actual make meaningful progress on it. Check our plan below.

Give us a feedback on our constitutional reform measures.

Rate this Policy.

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 4.4 / 5. Vote count: 11

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.